This week’s blog is all about POCUS. Since I started scanning seriously about a year ago, point-of-care ultrasound has become something of an obsession. When it comes to patients with undifferentiated shock or respiratory failure – or those with difficult IV access – it’s just such a useful skill for an acute medic to have.

That being said, it took me a long time for me to take the plunge and join the POCUS crowd. It can be really daunting to start off with, even if you’re lucky enough to work on a unit with a readily available scanner. Going on a beginner’s course is a great way to get started, but study budgets don’t always stretch that far in Foundation or IMT. But that shouldn’t stop you – provided you’re not using your early scans to guide clinical decisions, there’s no reason you shouldn’t just pick up a probe and give it a go.

There are some brilliant videos and beginners’ guides out there, but today I’m just going to focus on the things I wish I’d known when I was getting started and the things that got me hooked before I’d formally accredited.

Now, most people first turn to ultrasound for difficult cannulas and I was no different. I always assumed ultrasound-guided cannulation was something you needed to be trained to do, but the truth is ultrasound can be really useful even in the hands of the novice.

So what do you need to know?

When I was an A&E SHO, I remember our local ultrasound wizard showing me how to spot regional wall motion abnormalities in the parasternal short axis and all I kept thinking was “well that image is very pretty but how do I turn the machine on?” Thankfully one of my lovely regs was happy to point out the ON button later that day.

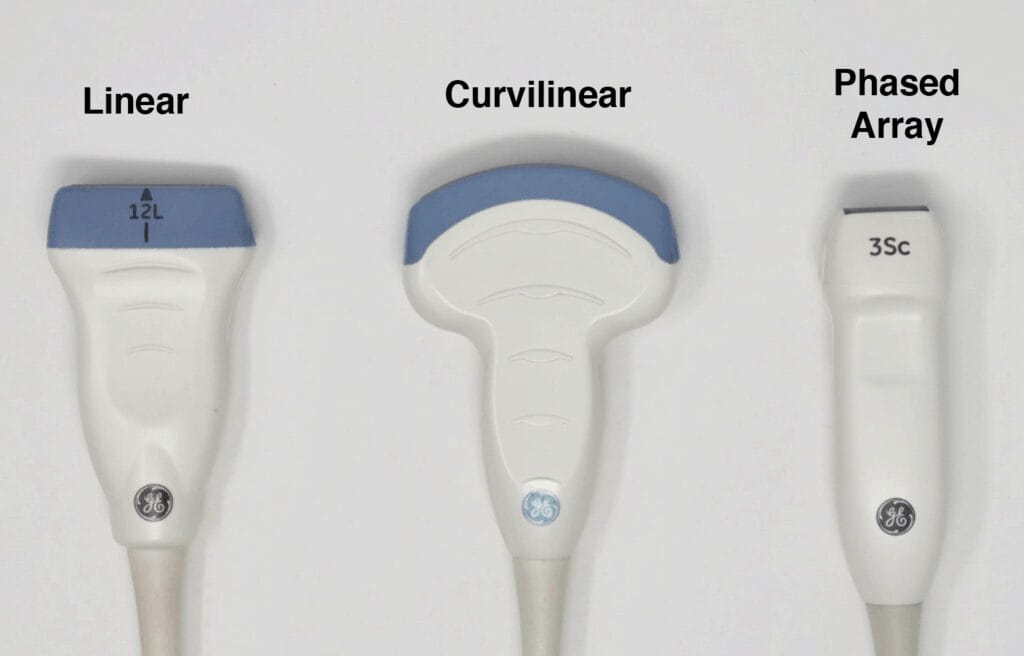

My next struggle was with probe selection. I remember grabbing the machine in a panic when I was struggling with a line in resus and failing miserably because I was using the big curvy thing rather than the little line thing.

As a general rule (and apologies to any radiologist for the gross oversimplification):

- Curvilinear for deep structures (mostly abdominal)

- Linear for surface structures (veins and arteries)

- Phased array for echo

So make sure your linear probe is selected. Use plenty of jelly. Get your patient in position – a properly tightened tourniquet and the magic of gravity often renders the ultrasound entirely redundant. Pop your probe in the antecubital fossa and see what you can see.

You’re looking for well-differentiated black circles – these are the blood vessels. Veins are easy to compress, while arteries gently pulse. Here’s my antecubital fossa, for example:

There are lots of videos out there that show how to cannulate under direct ultrasound guidance (I like this one), but sometimes this is overkill. Many times, the ultrasound has helped me find a vein I’m then able to palpate (usually after a few minutes of tourniquet and maximum gravity). I’m then able to put the machine aside and cannulate like we did in the olden days.

Now let’s say you’ve done a couple of cannulas this way. You’re starting to feel more comfortable with a probe in your hand and want to learn how to do more. Where do you go from here?

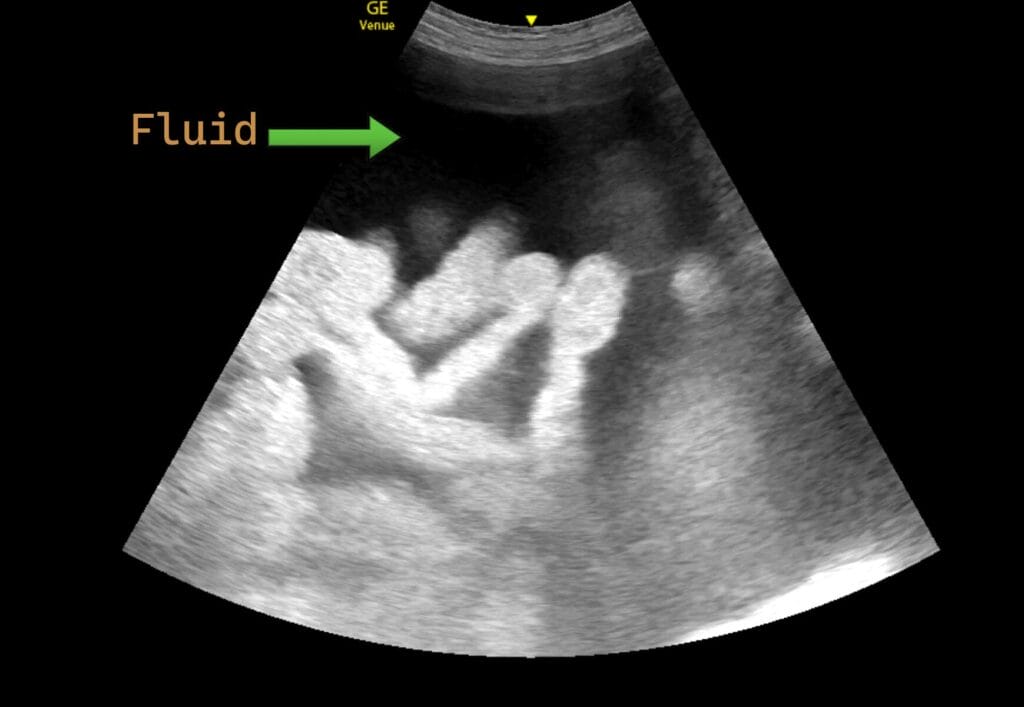

Next, I’d recommend an abdominal ultrasound on a patient with massive ascites. You’ll need the curvilinear probe to get the deeper views for this. Air bounces your ultrasound waves around, returning a meaningless grey fuzz, but free fluid transmits ultrasound waves perfectly, giving you a clear black space on the screen. The difference between a belly full of gas and a belly full of fluid is like night and day.

Not only is this an easy scan to get your head around, it’s also brilliant for finding the deepest pockets for that perfect ascitic tap. Similarly, smaller amounts of free fluid in non-ascitic patients can give hints as to the underlying cause of an acute abdomen.

I find abdominal ultrasound invaluable in patients with undifferentiated abdominal pain and have had several cases where it’s totally changed patient management. But ascites is great place to start.

Once you’ve scanned a few abdomens, you might be feeling brave enough to try a little echo. Now the heart is a complex organ, and getting the right views is definitely something that you need expert guidance for. But as a slightly clueless junior registrar, it was actually a cack-handed echo that really sold ultrasound to me as the wave of the future (pun very much intended).

I remember we had a patient with chest pain and an absolutely massive heart on their chest x-ray. Having conquered my fear of the linear and curvilinear probes, I thought I’d give echo a shot. I placed the probe just below the xiphisternum and angled up. Now I didn’t know much about echo, but I was pretty confident that there was meant to be fluid inside the heart, not all around it.

I grabbed the ED consultant, who chuckled graciously at my clumsy technique but confirmed that we were looking at a big pericardial effusion. I called the cardiologists and the patient went off to have it drained. Great result. I’ve since seen a couple more big effusions and on each occasion I’ve been grateful to have an echo probe to hand. Remember – POCUS works best as a rule-in technique and the safest thing you can do if you spot something weird is to ask someone else to cast an eye.

If you’ve got to this point in your ultrasound journey, it’s definitely time to invest in a good course and find a FAMUS mentor to get yourself formally accredited. I guarantee you’ll never look back.

References

Czeresnia, J.M., Alsaggaf, M. and Akselrod, H., 2019. A Case of Recurrent Pericarditis in Association With Asymptomatic Urethral Chlamydia trachomatis Infection. Infectious Diseases in Clinical Practice, 27(6), pp.360-363.